From Intel to Apple - Noncompetes are Bad Business

California's reluctance to enforce noncompetes has fueled trillions of dollars worth of entrepreneurism.

Please subscribe to this newsletter:

Many of the largest businesses in the world would have been stifled as startups if non-compete agreements were legal in California, which they seldom are. Part of the magic of both Silicon Valley and Hollywood is California’s near refusal to enforce these arguably anti-capitalistic economically harmful contract clauses.

Some background…

An Insufferable Bigot

The outbursts, public humiliations, and surprise lie detector tests should’ve been enough. After all, teenage Eugene Kleiner and his family hadn’t fled Hitler at fifteen to take orders from a blowhard bigot. Yet that was the exact situation he was facing.

A young Eugene wrote to his dad asking for advice and help.

Arthur Rock was a misfit. He joined the army hoping to fight Nazis only to be deployed shortly after Hitler surrendered. Rock graduated from Syracuse University, which he attended on the G.I. Bill then, immediately after, went to Harvard Business School, also on the G.I. bill. The Jewish son of an east coast candy store owner sat elbow-to-elbow with the very gentile sons of Captains of Industry.

After business school, Rock worked briefly as a securities analyst then joined the corporate finance department at Hayden, Stone & Company. He certainly wasn’t a blueblood Hayden or Stone but they quickly found a quirky job for him, finding funding for young companies. Rock quickly focused on the burgeoning high-tech sector where the fast-pace of change was fun but also challenging. Besides, nobody else wanted to help startups which, at the time, were typically funded by wealthy patrons much like an art production.

Kleiner Sr. circulated his son’s letter where it eventually found Rock and the two connected.

Along with a handful of other scientists, Kleiner had landed what he thought would be a dream job working with Nobel Prize winner William Shockley, co-inventor of the transistor. Shockley’s transistors were tiny “solid-state” materials that did the same job as vacuum tubes though they were far smaller, more rugged, faster, and required vastly less power. Transistors could revolutionize the world, dramatically shrinking electronic technology in terms of price, size, and power usage while increasing processing power. Because transistors were far more rugged they were also suitable for military applications.

After accepting the job, Kleiner found some serious problems. First, Shockley had been more of a business manager than an engineer on the transistor project. The actual scientists who invented the technology, John Bardeen and Walter Brattain, were not at all involved in Shockley’s business and weren’t especially thrilled with Shockley after the latter tried to steal credit for the entire invention.

Besides being a phony, Shockley was a verbally abusive overt racist micro-manager.

The Jewish refugee was uncomfortable working with a man who advocated a “Voluntary Sterilization Bonus Plan” and is quoted saying things like “Nature has color-coded groups of individuals so that statistically reliable predictions of their adaptability to intellectually rewarding and effective lives can easily be made and profitably be used by the pragmatic man-in-the-street.”

Then there were the working conditions at Shockley Semiconductor. Scientists were prohibited from talking to one another, Shockley randomly administered lie detector test, and, as if all the rest wasn’t enough, many of Kleiner’s co-workers didn’t believe Shockley would ever release a useful product.

A New Industry

Rock was intrigued. He’d heard about transistors and semiconductors and they sounded both exciting and commercially valuable. He hatched a plan with Kleiner to find him and his colleagues a new home. About three dozen companies returned blank stares, shaken heads, or hints of intrigue coupled with refusals to form a new group that might politically upset current employees focused on vacuum tubes.

Finally, Rock found Sherman Fairchild.

Sherman’s dad, George Winthrop, dropped out of school at 14 to apprentice as a printer. He soon purchased a newspaper and then branched into other business ventures. One promising business included employee timeclocks manufactured by the Bundy Manufacturing Company.

Bundy was good at innovation and manufacturing but struggled with sales so Winthrop formed a sales organization, the International Time Record Company. In 1911, International Time merged into a new entity, the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR). Eventually, in 1924, CTR was renamed International Business Machines … IBM. Winthrop was the Chairman and Sherman his sole heir.

Despite being fabulously wealthy, Winthrop was into technology and inventing. An aerial photography system did well. Rock convinced Sherman to fund a new division, Fairchild Semiconductor, then hire Eugene and the other engineers.

Altogether, eight engineers left Shockley for Fairchild in 1957. Shockley was livid, branding them the Traitorous Eight.

About the only thing Shockley had done well, albeit inadvertently, was move from the east coast, where technology businesses were based, to the sleepy college town of Palo Alto, California. Accustomed to life out west, the Traitorous Eight established Fairchild Semiconductor in the same area.

Life was vastly better at Fairchild. One of their major technology disagreements with Shockley was what material to use for their semiconductors. Shockley favored germanium; the others favored silicon. They created a silicon semiconductor then sold lots of chips, earning piles of money for both Fairchild and themselves. Other companies were formed nearby to focus on silicon chips and the area picked up a nickname, Silicon Valley.

Over time, the brainiacs became frustrated. Their stock options had vested leaving all the men relatively wealthy though money wasn’t their sole quest in life. Over time, they left to form or join other companies: National Semiconductor, Texas Instruments, and others. Eugene Kleiner left to help startup businesses and eventually co-founded the venerable venture capital firm, Kleiner Perkins.

Finally, tired of “east coast bureaucracy,” what was left of members of the Traitorous Eight again called Rock to help fund and form another new company, one they’d own that’d be managed on the west coast. He funded and helped form the business, naming it Intel.

Two Stinky Hippies

Rock kept funding companies and, eventually, moved west to help manage the new businesses. He became spectacularly wealthy but, despite the financial success, was always looking for new businesses to fund (at 94 years old he’s still regularly in the office).

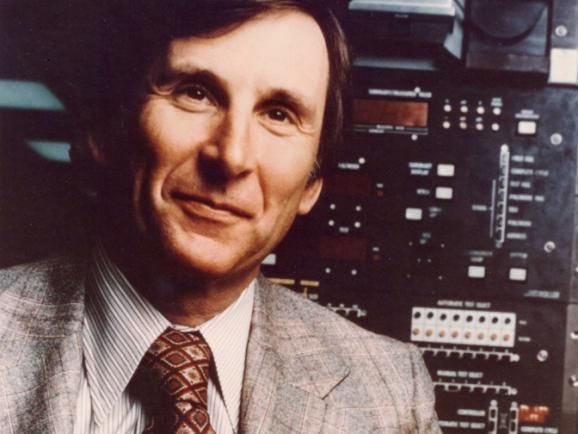

One person he kept in touch with was a young marketing manager at Fairchild and Intel, Mike Markkula. Thanks to stock options, Markkula had retired at the age of 32 and spent his days hanging out and checking out the new companies that sprung up around Silicon Valley. He’d invested seed capital into one of them and invited Rock to visit it at a trade show.

Rock described to me that trade shows were common in Silicon Valley back in the day. Businesses would show off their technology to one another, to customers, and to investors. Rock and Markkula walked through the stands, plenty of which were empty because the businesses folded before the show opened. None of the booths had more than a few people until they approached the one Markkula brought Rock to see.

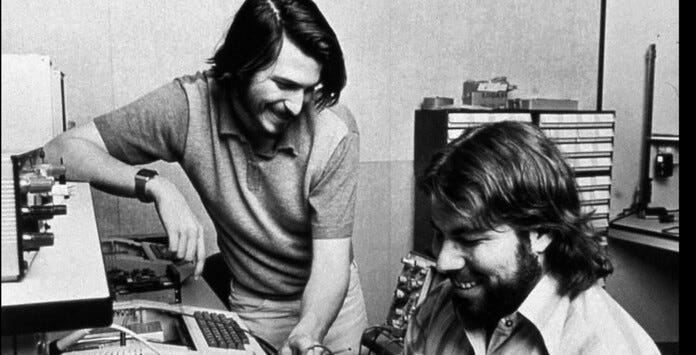

There was a throng of people excited about a new desktop microcomputer, one priced for and usable by ordinary people. Markkula pushed his way to the front with Rock and found, in Rock’s words, two stinky hippies both named Steve. The hippie movement from up the street in San Francisco had spread south and fused with the startup culture of Silicon Valley. One of the Steve’s was barefoot. They were absolutely not presentable; entirely unsuitable as businessmen.

Rock wasn’t happy with their demeanor but couldn’t ignore the mesmerized crowd. The barefoot one, Steve Jobs, did almost all the talking while the other, Steve Wozniak, seemed to have more of an engineering role.

To this day, Rock remembers he didn’t much care for either of these men. But the consumer interest around them was unmistakable and he thought their little computer might sell well. He invested and took a seat on their Board of Directors of their company, Apple, where his presence was a steadying and reassuring force for other investors.

Noncompetes

Except in rare instances, California does not allow the enforceability of non-compete agreements, contracts that prohibit an employee from competing with a business for some amount of time after the employee leaves.

If the state did allow non-competes, it’s virtually certain Shockley would’ve insisted on them stifling the Traitorous Eight and drowning Silicon Valley when it was still a baby. Furthermore, Jobs and Wozniak both worked for Atari at one point and Wozniak worked for HP when Apple was founded; non-competes would’ve stopped those businesses. Similarly, Rock, the man who coined the term “venture capital,” was able to go out on his own due to an absence of noncompetes. Kleiner’s firm went on to fund Amazon, Google, Compaq, Electronic Arts, Sun Microsystems, America Online, and Twitter among countless others.

Noncompetes allow slow, weak, and lazy businesses to continue in their ways rather than face competition from smarter, harder working, more nimble upstarts. They’re a relic of serfdom from the days when workers were locked in guilds through aristocratic rules about who could do what. These rules were designed specifically to stifle capitalism and competition.

Oftentimes, noncompetes are designed simply to harass and businesses frequently interpret the agreements well beyond their scope. For example, I was once falsely accused of breaking a non-compete when my wife took a job at a company that competed with one I’d been at. As if that wasn’t bad enough, the company with the non-compete had refused to hire my wife and called her “useless” (which is why I quit in the first place). I lived in California so rather than sue, the non-compete business started a slander campaign thwarting me in other areas (and, yes, in hindsight I should’ve sued for defamation).

There is simply no legitimate reason for noncompetes. Proponents argue noncompetes protect trade secrets but that argument is bogus. Trade secrets remain protected to the point that violating a trade secret is often not only a civil issue but also a crime; nobody is advocating that employees should be able to steal proprietary information.

Studies in the use of oppressive noncompetes show how ridiculous these arguments are. For example, Jimmy John’s sandwich shop used to insist on non-competes for its sandwich makers despite they had no secrets at all. Even if sandwich-making were somehow secret — a ludicrous proposition on its own — Jimmy John’s sandwiches are made in plain view of customers. Jimmy John’s dropped the practice after losing several lawsuits and a flood of negative publicity. The noncompetes were useless and harmful to the business, not helpful in any way.

People often wonder what the “secret sauce” behind Silicon Valley is. The weather is nice but there are plenty of places with nice weather. Stanford and Berkeley are great schools but, again, there are lots of Universities around the world. Lots of investment funds are available but capital also flows in New York, Chicago, London, Tel Aviv, and Singapore. A creative bohemian attitude? Nothing tops Paris.

One notable thing that sets Silicon Valley apart from other tech hubs is California’s refusal to enforce non-compete contracts. This is good for the economy, good for businesses that are forced to compete to keep their employees, and good for capitalism itself.

If you like this post, please consider subscribing:

If you like this article, please share it: