Standardized Interchangeable Parts: Breaking the Status Quo to Usher in the Modern World

How the invention of an unknown and disliked 18th century French gunsmith brought about everything from modern factories to an ability to read this post.

Every schoolchild knows about Gutenberg and his printing press, the machine which ended the Dark Ages. James Watt, inventor of the condensing steam engine, isn’t as well known though his work ushered in the Industrial Revolution. William Murdoch invented light from gas, rather than candles, enabling work and fun at night. My skunkworks project at innowiki.org briefly details lots of these inventors.

However, one stands above the rest despite that virtually nobody knows about him, Frenchman Honoré Blanc, also referred to as Le Blanc. His invention — the industrialization of standardized parts — literally fits the world together. It’s the reason that whatever device you’re reading this one is able to display the information the same way.

Few inventions rocked the world like Le Blanc’s standardized parts and few major inventors are lesser-known.

Briefly, standardized parts are the reason things fit together. Although we take it for granted today, before Le Blanc the vast majority of parts were individually produced and manually fit together. A “fitter,” who made parts fit together, was one of the most common jobs in Europe.

Sailors on ships realized different size cannonballs were a serious problem so they standardized cannons and cannonball sizes. Of course, cannons and cannonballs are large with relatively loose tolerances: standardizing them wasn’t especially insightful nor required enormous skill.

Le Blanc was a gunsmith with the French army and realized the method could be miniaturized for muskets. Muskets were vastly smaller than cannons and bullets require vastly tighter tolerances. Creating a standardized musket, where each part could be interchanged, was significantly more difficult than creating a standardized cannon.

During his time working on standardized muskets, Le Blanc was unpopular, relegated to a basement workshop and disliked by other gunsmiths who worried his invention would result in job loss. Despite a lack of funding, respect, and enthusiasm Le Blanc managed to perfect his invention by creating 50 muskets whose parts could be interchanged.

Interestingly, the earliest mention of these muskets and Blanc’s work came from American revolutionary Thomas Jefferson, who was Secretary of State in France at the time. France was (and remains) the oldest ally of the United States and Jefferson was given a demonstration of Le Blanc’s interchangeable parts. Locks for 50 muskets were put on a table and scattered around. Jefferson was told to randomly pick up various parts which could then fit together as fully functional musket locks.

The benefits of an interchangeable musket in war were obvious: not only could bullets be created the same size, much like cannonballs, but soldiers could also be taught to assemble a rifle and, if their rifle broke, could use parts from a different one.

Standardized parts were lower cost and higher value: the marker of a blue ocean invention.

Jefferson saw the benefit of the invention not only for the military but also for industry.

An improvement is made here in the construction of the musket which it may be interesting to Congress to know, should they at any time propose to procure any. It consists in the making every part of them so exactly alike that what belongs to any one, may be used for every other musket in the magazine. The government here has examined and approved the method, and is establishing a large manufactory for the purpose. As yet the inventor has only completed the lock of the musket on this plan. He will proceed immediately to have the barrel, stock, and their parts executed in the same way. Supposing it might be useful to the U.S., I went to the workman, he presented me the parts of 50. locks taken to peices, and arranged in compartments. I put several together myself taking peices at hazard as they came to hand, and they fitted in the most perfect manner. The advantages of this, when arms need repair, are evident. He effects it by tools of his own contrivance which at the same time abridge the work so that he thinks he shall be able to furnish the musket two livres cheaper than the common price. But it will be two or three years before he will be able to furnish any quantity. I mention it now, as it may have influence on the plan for furnishing our magazines with this arm.

— Thomas Jefferson to John Jay, Aug. 30, 1785

Jefferson realized that not only could weapons be standardized and created in bulk but anything could. He tried luring Le Blanc to the US but, despite hardships of the time, the Frenchman did not want to leave.

Jefferson’s demonstration was noted in some letters but many people thought it was an urban myth, an idea he came up with but made up the story about the French demonstration to pursue back in the US. However, thanks to the internet — and scanners (and Google) — we now know Le Blanc’s invention and demonstration were noted in the 1805 book, Memoire sur la Fabrication des Armes Portatives de Guerre by Gaspard Cotty. In a three-page footnote, Cotty describes how Blanc came to Versailles and demonstrated to Thomas Jefferson his standardized rifle parts.

Jefferson eventually returned to the US and brought the idea of standardized parts to Eli Whitney. Years before, Whitney had invented the cotton gin along with Civil War widow Catharine Littlefield Greene. Jefferson had been in charge of issuing patents but delayed issuing one to Whitney out of Jefferson’s personal distaste for patents. Realizing, in hindsight, he’d deprived Whitney of a fortune — as others knocked off the invention — he sought to make it up by offering a different invention, standardized parts.

With Jefferson’s help and his own reputation, Whitney received a contract to create standardized parts for muskets. He recreated the famous parts on the table demo that Le Blanc showed but historians agree it was rigged, with parts quietly marked that they knew fit together well. In any event, Whitney went on to create the Eli Whitney Armory. He never did perfect a standardized part musket though later generations eventually perfected the invention.

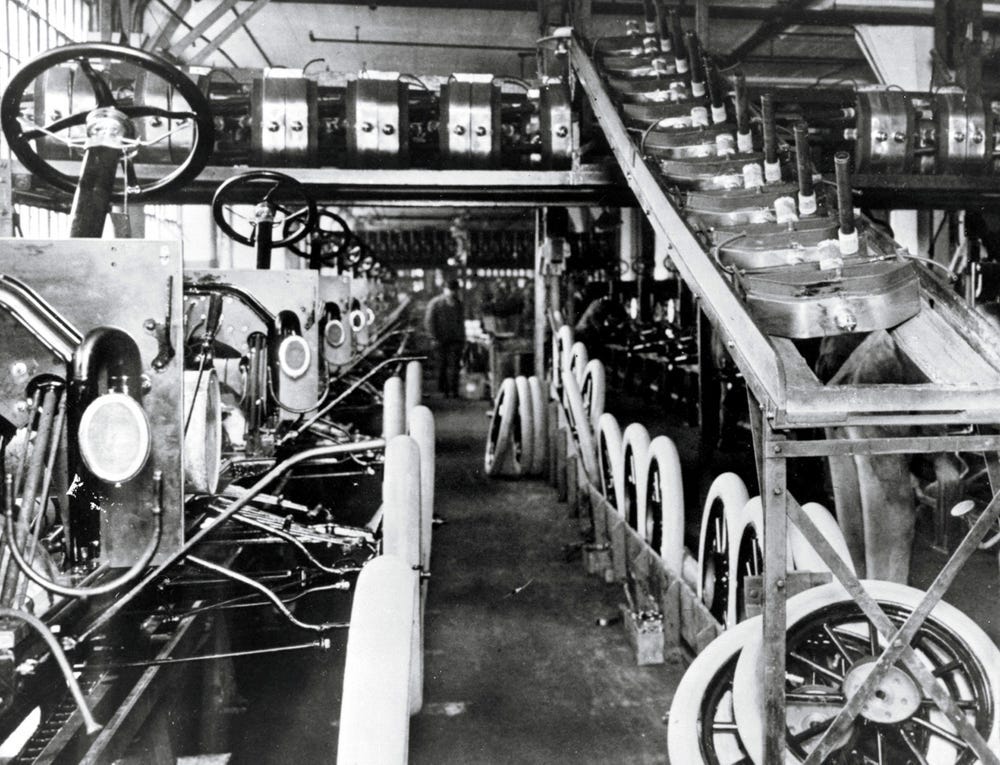

Standardized parts very much caught on in the US with the technique becoming known as the “American Manufacturing Method” or “American System of Manufacturing.” Among the most famous entrepreneurs to adopt the technique include Sam Colt, inventor of the six-shooter pistol, and Henry Ford, who famously insisted everything in his factories, including crates and pallets, were standardized and reusable.

Today, standardized parts are everywhere and keep the modern world moving. Cars, trains, and planes all rely on standardized parts. The internet and world wide web are nothing more than a set of “standards” digitally linking computers together. Look around wherever you are reading this and everything you see, whether composed of atoms or bits, is likely built using standardized parts. Despite this, Le Blanc remains largely unknown, a testament that great inventions can radically reshape the world yet leave their inventors almost entirely forgotten.